A few weeks ago I was flipping through the channels one night and came across the documentary Across the Pacific which is about Pan American World Airways and Juan Trippe’s vision of flying across the Pacific. I have always been fascinated by flying boats and as a child saved pictures of them from magazines. It is hard to believe just nine years before I was born it was thought impossible to fly across the Pacific to Honolulu. What is even more amazing is only 34 years after it was thought impossible, America landed on the moon.

In 2006, I attended the annual sea plane fly-in at Boulder City, Nevada in hopes of gathering material and photos for a magazine article. I was privileged to be introduced to Reid Dennis by aircraft restorer Dave Cummings. Reid had restored and modified the quintessential SU-16 Grumman Albatross. Reid graciously invited Dave Cummings, Larry Penrod, and I aboard his aircraft. It was well-appointed in leather and wood trim like that of a fine yacht. I noted on the cabin forward bulkhead a 1940s Life magazine under glass of a Pan Am flying boat. Reid said, “I always wanted to fly on a Clipper but they were gone before I got the chance.” The conversation continued and he said, “Let’s fly around.” We strapped ourselves in and spent the afternoon flying up the Colorado and making multiple landings on Lake Mead. What a thrill!

When we returned to Boulder City, I asked Reid if he would approve of me writing an article about his Albatross. He reached into the overhead bin and handed me a DVD, The Final Hours, which he co-produced about Amelia Earhart. It is a documentary of Linda Finch’s amazing retracing of Earhart’s flight 60 years later in a restored Lockheed Electra. Reid said, “This will help you. Call me anytime if you have questions. He said, I always wanted to fly around the world and when Linda Finch decided to retrace Earhart’s flight we flew as the support and camera plane.”

Up until that moment I did not realize that we had been out flying on the same Albatross which Reid Dennis flew around the world. The article I wrote was a success, and the next time Reid came back to Boulder City, my friend Penrod and I once again had the pleasure of flying with him and his co-pilot Andy Mcfee.

After watching the documentary Across the Pacific a few weeks ago, I recalled the conversations and the excitement of flying on Reid’s Albatross and our discussion of it not being possible to fly across the Pacific in the 1930s. Pan Am’s Juan Trippe believed it could be done, but navigation was one of the problems. Trippe consulted with Igor Sikorsky and Glenn Martin on developing large flying boats and Charles Lindbergh about long distance flying.

At that time, long distance flying over water in a small plane may have been possible but not for large commercial aircraft. There were not a lot of landing fields capable of handling a large aircraft, and landing gear technology was not sufficient to support a heavy aircraft. The alternative was flying boats. The weight of a giant plane could be spread across the entire bottom, which was supported by water. Pan Am conducted multiple proving and training flights with the Sikorsky S-42 into South America and the Caribbean. Master navigator Fred Noonan had created charts of the Caribbean and South America for Pan Am. A challenge was presented to him to create charts for Pan Am to navigate the Pacific in flying boats.

In the 1930s, Fred Noonan was one of the top— if not the best— navigator in the world. He charted the Pacific routes for Pan Am and trained the other Pan Am navigators. He flew multiple trips to Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Guam, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. Between his 22 years as a seaman and career with Pan Am, he was a legendary expert on navigation and the Pacific. His ability and knowledge of navigation was unquestionable. Even with more modern navigation aids he always carried a ship’s sextant and a chronometer on the flights. If there was any problem with powered navigation aids he had a backup. He had studied historical naval records creating a data base and acquiring incredible knowledge of winds, tides and currents which sailing ships had compiled for hundreds of years.

It eventually brought him to meet Amelia Earhart, which would cost him his life. She gained fame and he has been lost in the recesses of time. Not a single biography has ever been written about Fred Noonan and his storied life.

Fredrick Joseph Noonan was born in Chicago in 1893. His father was from Maine and his mother from London. His mother passed away when he was only four years old. In 1905, when he was twelve years old he went to Seattle. At only 17 he shipped out as a seaman on a windjammer. In only five years, he worked on nine windjammers and three steamers. He sailed around Cape Horn seven times, three under sail.

He became a quartermaster in 1911, Bosun’s Mate in 1913, and Bosun in 1919. He rose through the ranks to become an officer, Second Mate in 1921. By 1923 he was promoted to Chief Mate and received his Master’s license in January 1926. He served as a Merchant Marine during WW-I. He survived three ships that were sunk from under him by German U-Boats. All the while improving his navigational skills. His performance was noted as outstanding.

He married Josie Sullivan in 1927, and his life began to change. After 22 years at sea, he decided to start a new career. He had learned to fly in the late 1920s and received his commercial license in 1930. His intent was not necessarily to be a pilot but to become a long-distance aerial navigator. His knowledge of marine navigation was unsurpassed. In 1931, he received his marine license as “Class Master any ocean” which qualified him as a merchant ship captain. He was certified as a Mississippi river captain but went to work for The New York Rio Buenos Aires Line (airline). Shortly afterwards it was bought out by Pan American. He worked in Miami as a navigation instructor then station manager at Port-au-Prince and eventually station inspector for all of Pan Am’s operations.

This was a time when it was not thought possible to fly the 2,400 hundred miles across the Pacific. In 1925, the U.S. Navy had attempted it with two PN-9 Seaplanes. The navy positioned ships 200 miles apart for them to land and refuel. One of the planes failed after 300 miles. Commander John Rogers in the second plane made it to within 368 miles of Oahu but ran out of fuel while searching for the support ship. The Navy launched a massive search but could not locate the downed seaplane. Rogers and his crew skillfully stripped the fabric from the wings and made sails. Nine days later they were sited off Kauai.

The U.S. Army was next to attempt the 2,400 miles in June 1927 with a Fokker C-2 Tri-motor land plane. The army planned the attempt over years while developing flight instruments and navigation techniques. Lt. Lester Maitland and navigator Lt. Albert Hegenberger completed the first ever flight in 26 hours landing safely in Hawaii but not without radio failures and engine problems.

After their success James Dole, the pineapple guy, offered $25,000 for the first civilian crew to fly non-stop from the U.S. to Honolulu. The offer brought out every barnstormer and daredevil who could get an aircraft to Oakland. On 16 August 1927 the group of overloaded poorly maintained aircraft took off for the big race to Honolulu. Ten of the aviators died in crashes then two Army aviators died in a crash searching in the ocean for the lost participants. The event was a disaster, and the nation was in shock. It was declared that commercial flights to Hawaii were too dangerous and not possible.

Juan Trippe of Pan American was not deterred from his dream of commercial service across the Pacific and to the Philippines. The government even told Trippe that they would declare such an air service too dangerous to help him save face for Pan American. Trippe pressed on determined to open the Pacific to commercial aviation.

Iin March 1935, a stripped down Pan Am Sikorsky S-42 Clipper left San Francisco. The Clipper was under the command of Captain Edwin C. (Ed) Musick who was the first pilot hired by Pan Am. Musick had been a flight instructor for the Army, a Navy flight instructor in Miami and a Marine. He was undoubtedly the captains captain. He was was respectfully known as “Meticulous Musick” for his precision flying and double checking every detail and caution in pioneering long distance commercial flying. He flew every new aircraft Pan Am acquired and every new route.

The navigator on the first flight to Honolulu was none other than Fred Noonan. Captain Musick and Noonan were both the best at their profession. Musick and Noonan bunked together on all the flights they operated. Both men were quiet and did not care for publicity. Musick’s crews were tight-knit and had great respect for each other. Musick trusted and did not questioned Noonan’s navigational skill even though they were in uncharted areas and pushing the limits of aircraft of the day. Pan Am’s first flight across the Pacific was a success, and after 18.5 hours, they landed in Honolulu.

The return flight did not go as well, almost ending in disaster. After they were some distance from Honolulu the flight encountered extreme headwinds. Noonan calculated their ground speed at 96 miles per hour as the headwinds consumed excessive fuel. The Clipper held enough fuel for an estimated 23 hours of flight. At the speed they were traveling, it appeared they would not make it. The engineer leaned out the engines to use as little fuel as possible. After 22 hours and 59 minutes, the Sikorsky S-42 landed at Alameda, California. Once they shut down and dealt with the press, the fuel tanks were checked. There was only enough fuel in the tanks to wet the bottom of the tip of the dipstick.

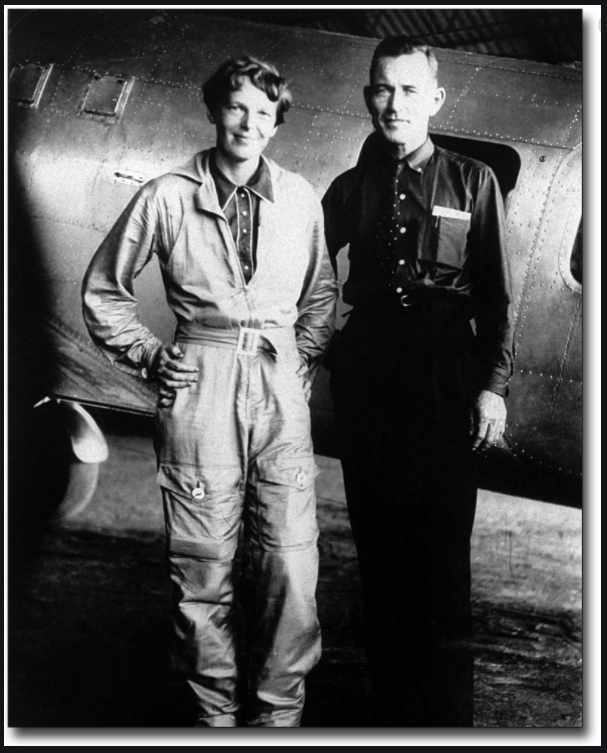

By 1937, Noonan had resigned from Pan Am. The stress and fatigue of the long flights and being away from home on round trips of weeks had taken their toll. He had already gained a place in aviation history creating charts and flying with Pan Am pioneering the Pacific. As a navigator, he could not advance any higher with Pan Am to increase his income. He had decided to capitalize on his talents by starting a navigation school. He was introduced to Amelia Earhart through mutual aviation connections in California. Earhart was an aviation celebrity generating tremendous attention. The publicity could improve Noonan’s chances of success with his navigation school. Also Earhart’s husband George Putman suggested him because he was the best in the world. Initially she was to have two navigators. Navy navigator Harry Manning was also engaged. However, he was soon doubtful of Earhart’s piloting skills.

There have been reports and speculation that Noonan may have been a heavy drinker. He lived during a time in America when most men drank. He had been a sailor and had lived a very dangerous life. If so, it appears he did not let drinking interfere with his professional ability. Captain Ed Musick would not have tolerated an inebriated crew member and Pan Am would not have placed an intoxicated crew member on a clipper to navigate with everyone’s life in his hands? Earhart despised drinking because her father was an alcoholic. Would she accept an intoxicated navigator for such a dangerous flight? It has been suggested that rumors were circulated about Noonan’s drinking to negate Earhart’s debatable flying skills. It appears reports of his drinking are more rumor and speculation than fact. There have been many conflicting opinions, but in reality we will never know because there is no conclusive evidence to suggest he was ever publicly intoxicated.

History has not given Fred Noonan a fair break. In my opinion, he lost his life because Earhart made multiple judgement mistakes. Earhart was not as skilled as publisher and husband George Putnam had made her out to be to the press and the world. Putnam had made millions publishing a book on Charles Lindbergh and was promoting Earhart as the female equivalent “Lady Lindbergh” for another book and a line of liberated women’s clothing. Historynet.com stated the following:

“There is no denying that Earhart had difficulty learning to fly. It took her more than 15 hours of flight time and nearly a year to solo……., and she had a number of mishaps afterward, most of them during landings. As one biographer noted: “Unfortunately, though highly intelligent, a quick learner, and possessed of great enthusiasm, Amelia did not, it seems, possess natural ability as a pilot.”

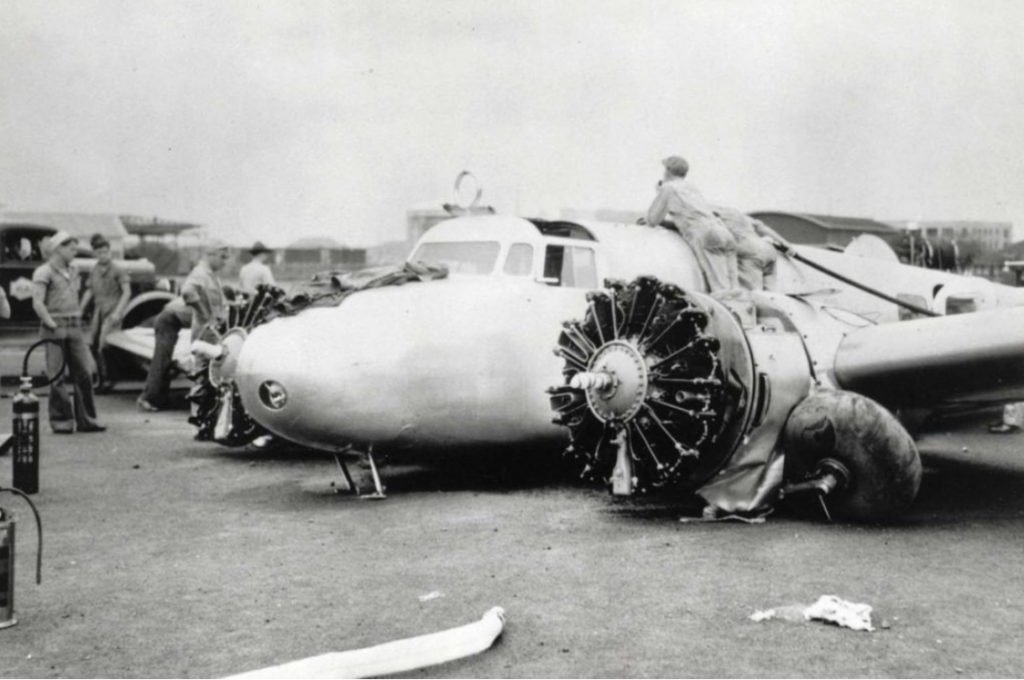

We know Earhart crashed at least four times prior to disappearing. She got lost on multiple occasions. Who knows why she flew solo from Honolulu to Oakland because it had been done before. It was probably to challenge her mediocre navigation skills. She probably could not have done it the other way without a navigator. When you fly across water to a continent if you have enough fuel you will eventually run into land. However, she still got lost 300 miles out and didn’t know where she was. You only have one shot flying across water to an island. If you miss it, there is no place to land. That is why when she did attempt the first westbound around-the-world flight, she took two navigators to reach Hawaii. Naval officer Harry Manning rode in the cockpit as radio operator. Navigator Fred Noonan rode in the back. He was supposed to get off at Howland Island and Harry Manning at Darwin, Australia, while she flew the rest of the way solo. At the last minute she asked Noonan to navigate around the world. On the first attempt, Earhart attempted to take off from Honolulu for Howland and ground looped the aircraft crashing. She returned to California to have the plane rebuilt and plan a second attempt.

After the Honolulu crash, Harry Manning, who was on leave from the Navy resigned when he arrived back in California. He used the excuse that his leave from the Navy would be up before they could complete the flight. Later he said “I had no faith in her ability as a pilot.”

The second attempt with Noonan was eastbound. She left California for Miami without telling her technical director. He found out she left on the radio. Her radio technician Joseph Geir had been pushing her to learn the new navigational equipment. Her effort was just a photo op. She received only one hour of instruction and never covered the direction finder or taking a bearing. At Miami, she decided to leave behind the life raft and vital radio equipment.

She and Noonan left Natal, Brazil for Dakar, Senegal which is the shortest crossing of the Atlantic. In the 1930s, navigation had a large margin of error. You could not rely on hitting your target. Noonan was known for meticulous planning. He used a proven method called “deliberate error method.” On the east bound, he plotted a 50 mile target area between Mbour and Dakar. That way when they made landfall, he knew which way to turn to find the landing field. Earhart refused to follow his instructions. She tried to fly direct drifting to the north then turned left, missing the target. She flew another 163 miles nearly running out of gas before finding a place to land. There is the fatigue factor element from boring hours aloft in a noisy cabin probably smelling fumes. However, this should not interfere with setting the course given to you by the best navigator in the world. The next day they had to fly to Dakar to fuel up for the next leg.

There were problems all along the way. When they got to Calcutta, Earhart called Putnam and said she was having personnel problems (She probably wasn’t listening to Noonan). She went to visit Buddhist temples, and he went to a bar. When they got to Darwin, she left behind their parachutes and survival equipment.

The leg from Lae, New Guinea was the longest leg over water. Earhart wrote back to Putnam, “I need to give up long distance stunt flying.” She had made the same statement to famed aviatrix Jackie Cochran before leaving.

Noonan insisted they leave at exactly 12:30 pm. He knew the sun rose at the equator at precisely 6 am the next morning. Baker Island is just 51 miles north of the Equator, so he could take his readings and know exactly where they were. Once again, he used the deliberate error method. This time he shot a course between the two islands— Howland and Baker— for a bigger target. That way, at altitude you either see both of the islands or see one and know which way to turn to Howland. We will never know definitively but based on the Natal – Dakar incident and Earhart’s history of drifting to the left, it appears she did the same here setting a course direct to Howland reducing the target to a dot in the Pacific. Earhart had ignored Noonan before, and missed Dakar. She had also left behind the 250-foot trailing wire antenna, which would have made it possible to communicate.

It was reported in Australian newspapers they could not properly set the aircraft chronometer because of static interference. However, Noonan carried a key wind chronometer and a sextant. There were also reports of a fuel line repair at Lae and speculation it was still leaking reducing the fuel supply. Furthermore there appears to be photo evidence that the directional antenna was knocked off when the rear of the aircraft dragged on takeoff from Lae. The fact is they were close enough to Howland for the Coast Guard to hear her transmissions discounting the suggestion they ran out of fuel before being in the area.

When they were 200 miles from Howland, she could not hear the Coast Guard ship Itasca. The ship could hear her and was trying to get a fix on her transmission. The Coast Guard calculated she got within 60 miles of Howland but was probably north and couldn’t hear the ship. It is believed from her radio transmissions she was flying 30-mile circles north and west of Howland until they ran out of gas. Where ever they went down there was not chance of survival. She had left the life rafts behind.

The mystery of Earhart’s disappearance continues today. But history didn’t give Fredrick Joseph (Fred) Noonan the same courtesy. Fred Noonan earned a place in history with great navigators like Ferdinand Magellan, Juan Sebastian Elcano, and Sir Frances Drake. However, if you pull up a list of great navigators it includes Amelia Earhart who often got lost and had questionable navigational skills and has no mention of Noonan who should be remembered. Still, navigational expert and historian Bowen Weisheit, who attended the same navigational school as Noonan and others agree that Noonan was the top navigator in the world at the time with a reputation to prove it.

On Howland island a twenty foot deteriorating stone light tower was converted to a primitive monument with the plaque “Earhart Flight 1937.” Sadly, there is no mention of Fred Noonan.

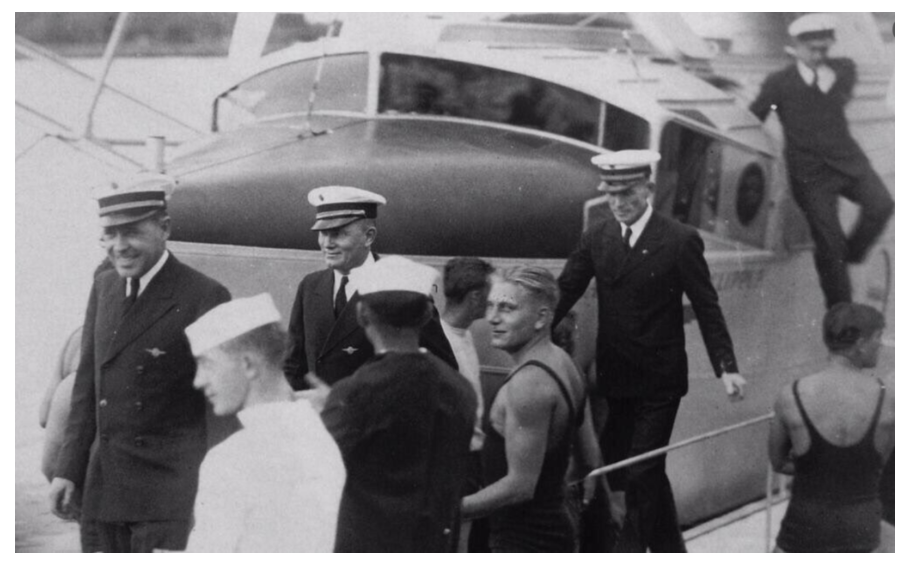

Photos of Fred Noonan: Pan American World Airways

Furthermore, I’m Just Saying

I am tired of periodic new theories or circumstantial evidence that the wreckage of Amelia Earhart’s plane has been found and the mystery has been solved? It appears the most recent idea is that parts of her plane are on Nikumaroro Island (formerly Gardner) in the Phoenix Islands.

No doubt airplane parts are scattered on islands all over the South Pacific from the action of World War II. So, there may be airplane parts on Nikumaroro, but I seriously doubt if they are from the Earhart – Noonan flight.

We are asked to believe that out of the three million plus square miles of the South Pacific, where the total amount of land is a series of dots of islands, that they ended up on another island 400 miles south. I submit, there is too much water. Let us review the facts we know.

Amelia Earhart had trouble navigating. In her previous flights, she charted her course direct point to point. It is a fact, she tended to drift to the left over distance. Early in this flight from Netal to Dakar, she ignored Noonan’s course and tried to fly direct. She missed the target by 200 miles to the north (left) and almost ran out of fuel.

Fred Noonan was recognized as the best navigator in the world at that time. He used the “Deliberate Error” method when charting a course, especially over water where there are no reference points. The method requires you to pick another point near your target and chart a course between them. That way, you have a larger target instead of a dot in millions of miles of ocean.

Noonan picked Baker Island, which is 43 miles south of Howland and 12 miles from the equator. This gave him a target range of at least 109 (200 north-south) miles from altitude. Depending on where they were, they would either see one or two islands and know which way to turn to land at Howland. Noonan specified that they take off from Lae at a specific time because the sun rose on the equator that morning. He could take a reading and know exactly where they were. When they were near Howland, the Coast Guard cutter could hear their radio transmissions. Earhart’s radio antenna was not capable of transmitting more than 200 miles, so they were in the area of Howland. Up to this point is fact!

We can only speculate that Earhart ignored Noonan and tried to fly direct to Howland, even though it is reasonable. If she drifted to the left (north) as she had done before, they would have been north of Howland flying in circles. It is preposterous to even suggest that they crashed on Nikumaroro, which is 400 miles south-south-east of Howland. Earhart’s antenna was not capable of transmitting more than 200 miles. The Coast Guard could not have heard her calls from that distance.

Fred Noonan was the premiere aerial navigator in the world in 1935. He was quite simply the best. Noonan today is sadly but a footnote not only to the Pacific crossings that he did with Pan American Airways but also with his around the world flight with Earhart.

The “voice” of Fred Noonan is on Twitter and Facebook. Some care to keep his accomplishments and memory alive.

twitter.com/frednoonan

https://www.facebook.com/FredNoonan1937/

Always looking for a flying challenge to learn from, I read up on this fateful flight, and decided to see if I could recreate it in X-Plane, using only Line of Position sun navigation and the Deliberate Error Method, aiming to the northwest of Howland, which others have speculated they probably did when they discovered at about 200 miles away from Howland that their direction finding radio didn’t work as expected. I realize I’m doing this in a simulation, but I don’t have resources to see how effective it actually is in real life, for such a tiny target. Nevertheless, I had my doubts initially, but was very surprised how well it really works. Briefly, I found Howland every attempt, tracking within 5 miles east or west, regardless of the unknown weather conditions I randomly set while flying, which I made progressively worse each try. I made sun angle measurements with an accuracy of only one half a degree, which is a huge error for sun navigation, but I updated my sun angle measurement every 5 minutes after my first turn southward onto the line of position, in order to adjust my track to ensure it was still correct for that time of day. That’s critical. The Line of Position heading may not change, but its location on the surface of the earth is rapidly running westward as the sun rises in the sky. There is very little time to make a decision. You have to plan ahead, pre-recording your estimated arrival times, so you can lay out these 5-minute sun angles to make your turn without having to do too many computations at a critical minute, basically just interpolating angle and time, if you reach it between your pre-planned intervals. On average, after my first turn southward, I had to change course briefly two times while closing on the island, narrowing my initial error each time, before I could say with confidence I had nailed the line of position; then five minutes later I’d see Howland and safely land. I started a stop watch when making my initial turn, and based on indicated airspeed and my maximum deliberate error, had a rough idea when I should reach the island; saw it every time. My conclusion is that it’s hard to screw this up; and certainly someone with Noonan’s experience would not have. If your clock is set accurately to GMT and your sun almanac is correct for Howland GMT, and you’ve pre-planned your line of position arrivals for sun angle and time at a reasonably tight interval, five minutes was reasonable for me, clouds are the only issue, if they are too thick to sight through to see the sun. And there you have it. The Deliberate Error Method with Line of Position is an elegant and accurate navigation technique. But you have to be able to see your celestial target, in this case the sun. Tragically, if instead they had deliberately offset to the south of Baker Island for a turn northward, there were reportedly no clouds in that location; only to the northwest where they were headed, and their radio didn’t work, so nobody could warn them. They came to a fork in the road, and as fate would have it, cloud cover was a 50:50 proposition that day.

Great mini-biography on Fred Noonan. Thanks for putting the time and effort into researching it.

Thank you for putting so much effort in testing Noonan’s navigational skills. Noonan spent years refining this method which had been used for centuries in sailing. He was known for tedious preparation. In my opinion you have reinforced the theory that they would have made it if Earhart had followed his course. She had a history of making the same mistake only this time it was fatal.

I am curious how you “know” Earhart ignored Noonan’s instructions on the flight to Howland, especially since you are making these claims as statements of fact. Do you have any evidence for these claims?

Hi: I was part of the team that made “The Fina Hours,” and spent time both on the ground and in the air with Reid and crew in N44RD. Also put some video gear abourd Finch’s a/c prepping it before “World Flight ’97.”

What struck me about the situation Fred must have been dealing with was that his only way they had to communicate in flight was via notes passed over the massive fuel tank installed between him in the back and Earhart up front.

Your point about Fred’s tried and true method of deliberate error (aka “aim off”) is well-taken. He certainly would have given her a course that allowed for a positive decision when they reached the target line of position.

I agree with you that Earhart likely pulled the same trick that almost got them lost in Africa.Thow in the fatigue factor from hours aloft in a noisy cabin, (probably breathing gas fumes), along with the isolated conditions they were both functioning under, it was a tough environment for them both.

One thing you didn’t mention in you article – which was very good – was that Ed Musick looked after Fred through thick and thin during their working time together. He trusted Fred, and I’ll bet that when they flew together the whole crew was probably a tight-knit happy crew. Flying with Amelia Earhart, fulfilling the schemes that she and her ambitious husband had driven her to, must have seemed like a miserable alternative to Fred Noonan.

He deserved better.

And no financial compensation for him or his wife, either outright or through life insurance. Sad to say, if Fred were a drinker it affected his judgement here. Especially going up for thousands of miles with a pilot whose reputation preceded her.

This article should be preserved in aspic to ensure future generations can cleanse themselves of the PR boy’s version. Excellent work.

Although Fred Noonan did not receive the recognition he deserved worldwide for his navigational skills and many people don’t know his name now, in 2026, as a former, career, flight attendant with Pan Am, hired in London in 1964, I remember well that in my initial training class at JFK in May of 1964, that our class of 15 stewardess trainees were told about Fred Noonan and how in his years with Pan Am his navigational abilities developed the routes for Pan Am to fly to points across the Pacific.