Most of the ‘Legacy’ airlines were founded by visionaries with names synonymous with the carrier. Juan Trippe was Pan American Airways. He pioneered commercial flying in the Caribbean and South America with a vision of flying across the Pacific. General Motors acquired Eastern Air Transport (later Eastern Airlines) from North American Aviation Corporation (NAAC), which had collapsed during the Great Depression. Eddie Rickenbacker was appointed as General Manager of Eastern in 1934. NAAC also owned an interest in TWA, which was acquired by the Atlas Corporation. Rickenbacker soon put together a group of investors to acquire Eastern Air Lines and became president in April 1938. By 1940, Eastern was the dominant airline east of the Mississippi.[1] William Boeing formed Boeing Air Transport (BAT), the basis for United Airlines, to fly mail contracts. It was merged with several other carriers to become United Airlines. Banker William Patterson took the helm at United with a vision of creating a ‘Trunk Carrier,” which he called “The Mainline.” Jack Frye of TWA envisioned non-stop transcontinental service. TWA inaugurated transcontinental mail service in 1930. It was the third-largest airline before WW II. Howard Hughes gained control of TWA in 1939. In 1940, the airline took delivery of the Boeing 307, the first pressurized commercial airliner. In 1945, as a reward for TWA’s air transport operation during WW-II, TWA was granted routes to Europe and India to compete with Pan Am. These men were the titans of commercial airline empires from the 1930s onward for decades.

Transocean Airlines

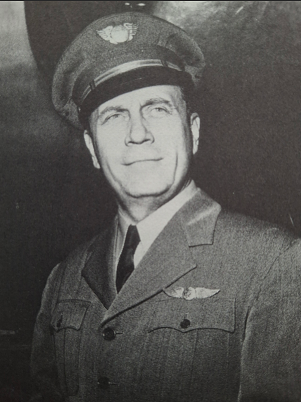

At the end of World War II, another visionary arose who built an aviation empire, but few people know his name. Orvis Marcus Nelson founded Transocean Air Lines, a supplemental carrier, which became larger and had more aircraft than some of the legacy carriers.

Before the war, the technology of commercial aircraft development had moved slowly. New airliners were being developed, but were coming online at a snail’s pace. When America was attacked in 1941, the military needed transport aircraft. The airliners in production were commandeered for the war effort. Commercial traffic was disrupted, and civilian airline pilots were contracted to fly military transport missions.

Pan Am conquered the Pacific only seven years earlier, in 1935, when it was not thought possible to fly across the Pacific. The necessities of the war effort changed aviation forever. A new age of advanced aircraft technology was dawning, but it would take time for it to translate into commercial travel. The war soon fostered the need for jet transports, which brought a new age in commercial aviation. Initially, it was believed that jet-powered aircraft would be too dangerous for passenger travel. When the war ended, aircraft borrowed from the airlines (DC-3, DC-4, C-46) by the military were returned and converted back to passenger configurations. It was quite common for former military pilots returning to civilian life to form small airlines with their flying buddies and purchase one or two surplus transports. Many of them fell by the wayside in a very short time.

Orvis Nelson was one of those pilots who dreamed of creating an airline. He has a vision and was not afraid to take chances. He was a daring adventurer and a deal-maker who lived a life that pales fiction, but history has lost his contributions to the airline industry in the recesses of time.

Nelson was born in Tamarack, Minnesota, in 1907. His education was in sporadic periods between working in the lumber business. He was fascinated with aviation. When Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic in 1927, Nelson was inspired to join the U.S. Army Air Corps. He learned to fly and was assigned as a technician on the aerial survey project in the Philippines. In short order, he became disenchanted with Army flying because he could not fly as much as he wanted. Nelson bought his way out of the military, as was common then under the ‘exemption by purchase’ program. This allowed him to enroll in Franklin College, where in 1932 he earned a degree in Mathematics. In 1935, he resigned his commission to take a position with United Airlines. Nelson was a maverick but earned the reputation of being a leader and was a very capable pilot. (Army Air Corps 1932-1935, United Airlines 1935-1946, Transocean Airlines 1946-1960, Air Systems/ Aeronaves de Panama 1962-1964)

Being an airline pilot was a dangerous profession in the early years, which needed standards and regulations. This led to the formation of the Airline Pilots Association (ALPA) in Chicago by David Behncke in July 1931. During the 1930s, Nelson built a reputation as an outstanding pilot flying for United in DC-2s and DC-3s. He knew firsthand the dangers and became concerned with flying rules and standards.

When WW-II began, United received a contract to fly for the Air Transport Command (ATC). Nelson was assigned as a civilian pilot to Alaska. He soon transferred to the California-Hawaii route. In 1942, he became vice-president of the airline pilots’ union, ALPA. One of his goals was to have pilots who flew military contracts be commissioned as military officers. The CAB and the military ruled against him, but he continued to fly for United.[2]

After the war, Nelson saw great market potential in the Pacific. He and fellow pilots recommended that United expand operations into Asia by starting an airline in Japan. With commercial air service destroyed by the war, he believed there was great potential in Asia for United. Nelson presented his plan to United for a Far East Division. United’s president, William Patterson, rejected the idea, which also required approval from Gen. Douglas MacArthur. He did not approve, stating it was not advisable to have Americans operating an airline in early post-war Japan. Unfortunately, United did not realize the potential in Asia until it purchased the Pan Am Pacific division in 1985.

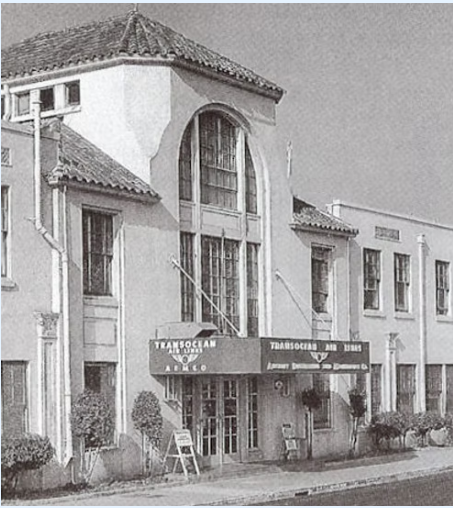

On 09 March 1946, United’s vice-president of operations, Jack Herlihy, asked Nelson if he would be interested in becoming a sub-contractor for United on military contracts from San Francisco to Hickham, AFB at Honolulu. United had been pressed by the government to take the contract, but company officials decided to contract out. Nelson scrambled to obtain surplus C-54s and initially started as Orvis Nelson Air Transport (ONAT). United assisted in obtaining aircraft from the government. On 01 June 1946, Nelson incorporated as Transocean Air Lines (TOA) and immediately began operating military support contracts in the Pacific.

Nelson soon challenged Pan Am’s routes from the U.S. West Coast to Honolulu and Guam with commercial charter traffic. At the end of 1946, United gave up the military contract. Nelson bid on it as TOA but lost out on the San Francisco – Honolulu service to Robert Prescott’s Flying Tigers Airline. Transocean had been flying government contracts in the Pacific since the end of the war. This was a devastating blow for Transocean, but Nelson somehow managed to assume TWA’s contract to train Philippine Airlines crews and operate trans-Pacific charter service.[3]

During the next few years, Nelson’s primary customer was U.S. military charters, but he wrangled other charters to transport anything all over the world. In 1947, he received a contract to provide flight crews and training for the newly formed Pakistani airline, Pak-Air. Transocean then initiated a twice-weekly Caracas – Rome service in 1948. The CAB charged Nelson and Transocean with illegally transporting passengers on scheduled service overseas. Nelson maintained it was outside the CAB jurisdiction. Then Nelson received a contract from the Chinese National Air Force for Transocean to ferry 157 Curtiss aircraft from the U.S. to Shanghai.

Nelson created other support companies under the Transocean umbrella, but his primary focus was building a large international commercial airline. His experience in flying throughout the Pacific during WW II was priceless. It was what he knew that gave him the edge in obtaining government contracts which was his lifeline. His relationship with the government became a double-edged sword. He operated on a thin margin with an older fleet of compromised poorly maintained surplus airliners. He was no stranger to “black ops” intrigue around the world. The military was pleased he was doing their heavy lifting and dirty work, but the CAB was continually threatening because of maintenance practices and his stepping on the toes of the legacy airlines and, in some cases, transporting more passengers and cargo. Transocean’s biggest customer became the U.S. military. During 1948-49, the U.S. military committed all its resources to the Berlin Airlift. Transocean was contracted to fly many of the Military Air Transport Service (MATS) supply routes in other parts of the world.

South Pacific ‘Trust Territories’ Air Service

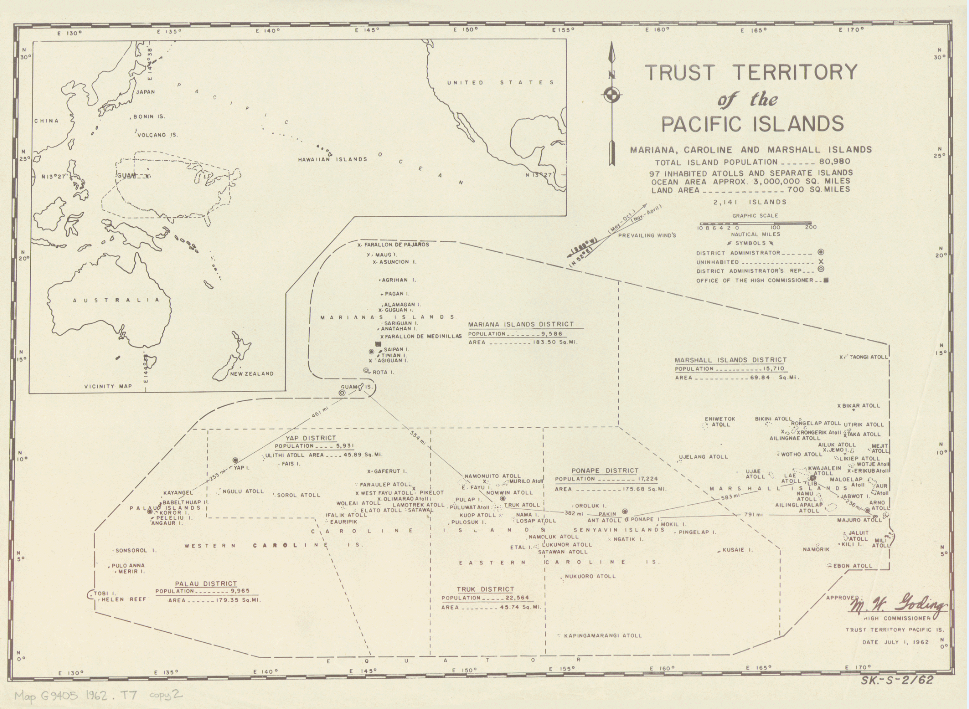

Possibly Nelson’s greatest achievement is not widely recognized. After the war, the newly established UN struggled to find a way to provide aid and services to the war-torn remote areas of the South Pacific. The Japanese had occupied the islands of Micronesia for nearly 30 years and had provided no services to the local people. Orvis Nelson had frequently flown to Guam and throughout the Pacific during the war for the ATC. The U.S. Navy was providing irregular humanitarian service to Micronesia after the war. In 1948, Nelson was approached by the U.S. government to propose a plan to provide air service to the Trust Territories of the Pacific. The challenge was to provide service throughout the 3,000,000 square miles of the Trust Territory, which included the Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana Islands. There were over 2,141 islands, but only 84 were inhabited by about 52,000 people. The Navy humanitarian support service was a sporadic operation that did not function like a commercial airline.

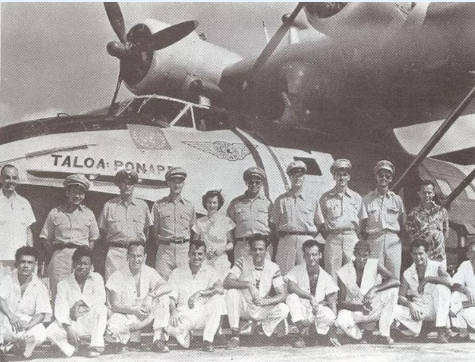

Nelson picked experienced Navy PBY Captain Edward Landwehr, who was only 25 years old, to develop a plan. The service could only be operated with seaplanes because of the lack of airfields. It took several months of planning to establish a supply line, find housing for the 30-man crew, overnight layover quarters, set up maintenance bases, fuel storage, and procure aircraft for an airline-type operation. Transocean was awarded a contract that seemed impossible.

In 1949, the Department of the Interior took over the Trust Territories of Micronesia from the Navy. The Navy agreed to transfer four PBY-5 flying boats for the 1,800-mile route. The PBY-5 cruised at 125 mph. It carried ten passengers, who were mostly medical personnel, government planners, diplomats, and financial planners, plus medical supplies, mail, currency, and cargo of all descriptions.

Service began in 1949 with Transocean contract crews. Within six weeks, every flight was booked full. International passengers arrived at Guam on Transocean DC-4s and transferred to the TALOA (Navy) seaplanes. The five-day 1,900-mile flight eastbound to Majuro departed on Mondays from the Transocean base at Agana Field, Guam. The first leg was 633 miles to Truk Island, where they remained overnight. The next 460-mile second leg was to Ponape, where they had to land in the water because there was no airfield. After an overnight, the next leg of 622 miles to Kwajalein for fuel and 268 miles to Majuro. The return flight departed every Friday. Transocean also operated DC-4s similarly out of Guam, north to Saipan, and southwest to Yap and Koror, where there were airfields.[4]

Transocean was contracted in 1949 to provide crews and technical support for startup airlines Air Jordan and Air Djibouti. When the Korean War broke out in June 1950, Transocean was already flying supplies and personnel for the military from the West Coast to Honolulu and other Pacific islands. Nelson’s contract with the military rapidly grew during the Korean War. Between 1950 and 1953, Transocean was operating more than ten percent of all U.S. military transpacific supply flights to South Korea. [5]

Although Transocean was a supplemental carrier, it had grown to the size of U.S. scheduled airlines that were protesting to the CAB. Transocean derived fifty percent of its revenue from government and military contracts. Nelson was caught in a government squeeze. On one hand, he was being offered lucrative government contracts to fly to the most remote parts of the world, supporting government projects and the Korean War. On the other hand, the CAB was continuously threatening to shut him down because of his size as a supplemental carrier.

The Transocean Trust Territory flights out of Guam began in 1949 with the loaned Navy PBY-5 aircraft that were operated by TALOA. On 01 July 1951, the U.S. Department of Interior took over the administration of the Trust Territories of the Pacific (Micronesia), which had been under United Nations direction. Transocean was the successful bidder to continue operating the scheduled Trust Territories airline for the 3,000,000 square miles of air service.

The war-weary PBYs were problematic and needed to be replaced by a more suitable airliner-type aircraft. In June 1954, the CAA certified the superior SA-16 Albatross seaplane for commercial service. It was slightly faster cruising at 154 mph. The Air Force transferred two Grumman SA-16 Albatross aircraft to the Trust Territory Service. The aircraft were painted in a very smart-looking Transocean livery.

In 1951, Nelson was contracted to provide aircraft, crews, and training to reestablish commercial air service in Japan by getting the country’s national airline, JAL, up and running. In 1952, Nelson negotiated a contract with Scandinavian Airlines to operate the carrier’s European cargo service. Then in 1953, Transocean received authority from Afghanistan to operate the Kabul – Kandahar – Jerusalem – Cairo service. Nelson’s Transocean was flying under contract for JAL, Philippine Airlines, Scandinavian Airlines, Air Jordan, Pak-Air, Trust Territory Airline, and military contracts all over the world when they received a contract in 1953 to develop an Iranian national airline.

Nelson also supplied Transocean aircraft for Hollywood movies. In 1953, two aircraft were leased for John Wayne movies, Island in the Sky and High and The High and Mighty. During this same time, Nelson supplied the U.S. Government with DC-4s to fly thousands of pounds of gold bars from Japan to New York City, worth $6.2 million ($588,114,295 today). One of his most unique missions was in 1954. He contracted for operation “Noah’s Ark,” a shipment of 550 rabbits, 30 goats, and two million bees to Pusan, South Korea, to help rebuild agriculture after the destruction of the war.[6]

The unregulated Transocean had gotten too big. The executives of U.S. scheduled carriers were complaining to the CAB, and lawsuits were being filed. Nelson had turned a supplemental contract airline into a worldwide conglomerate. From 1953 to 1956, Transocean was more than the largest “Supplemental Air Carrier.” It had a fleet of 114 aircraft, and at its peak, 6,700 employees with 57 bases worldwide, including 16 contract maintenance bases in Europe, which serviced many other airlines. In 1953, Richard Thruelson published a history of Transocean listing the following assets: Transocean…

… owns and operates one of the country’s largest aircraft and engine overhaul facilities in Oakland, California.

… staffs 28 bases around the world (16 in Europe).

…operates two airport restaurants.

…operates a hotel on Wake Island.

…owns and operates a printing company in Oakland (supplies to all Transocean companies printed materials).

… owns a heavy construction company engaged in building airports, roads, and bridge construction.

…operates a barber shop (full-service facility for flight crew layovers).

…owns and operates a chemical plant.

…operates a worldwide crop-dusting operation.

…runs a Dodge automobile dealership and service company in Okinawa.

…owns a worldwide trading company that deals in such diverse commodity items as fish meal and Swiss watches.

…owns and operates the TALOA Academy of Aeronautics (training for pilots, cabin crew, mechanics, flight ops, weather, and navigation.

…operates an industrial development division that manufactures aircraft components for the U.S. Navy aircraft.

…consults and supervises the reactivation of Japan Airlines.

…owns a ten percent stake in Philippine Airlines, which it reactivated after WWII as a worldwide carrier.

…operates the 3,000,000 square mile air transport system serving 1,300 atolls and islands for the Department of the Interior, Trust Territory Airlines of Micronesia.[7]

In addition, Transocean operated airlift supply flights from Africa to desert oil outposts of the Middle East; Operated a shuttle service from the U.S. West Coast to the Philippines connecting to Philippine Airlines; Flew regular charter service between Great Britain and Canada; Operated twice daily scheduled service between Rome, Italy, and Caracas, Venezuela.

The U.S. government/military and the Department of Interior were very favorable to Nelson and Transocean when the airline was needed for supply lines, humanitarian missions, and special operations (covert) services, but were silent when Nelson needed CAB route authority. By 1957, Nelson was experiencing financial problems because banks were being pressured to withhold loans. The Transocean fleet was made up of refurbished WW-II aircraft, mostly DC-4s. The airline was operating on cash flow from its other business for some time. Without CAB approval for scheduled service, Nelson could not obtain loans to upgrade the Transocean fleet.

Airline service throughout Asia was served primarily by Pan Am, but they were being challenged by other carriers. Nelson attempted to obtain CAB certification to serve multiple Asian cities through Hawaii and Guam. The Transocean fleet would need to upgrade to newer long-range airliners. The CAB denied Nelson’s first request in 1955. Nelson was struggling to stay liquid while challenging aviation regulatory restrictions.

Nelson’s successes and his troubles did not go unnoticed by corporate raiders. The Transocean downfall began in 1957. To raise capital and save the airline, Nelson was forced to sell 40 percent of Transocean to Floyd Odlum’s Atlas Corporation. With the influx of cash, Nelson was able to strike a deal for 14 surplus long-range Boeing B-377 Stratocruisers, which were available at bargain prices. The major carriers (Pan Am, United, Northwest, and BOAC) had phased out the giant airliners. They were big, heavy, luxurious, and smooth flying, and had low hours on the airframes. They were known as the “Cadillac of Propeller Aircraft” because the passengers loved them. However, they were fuel hogs that suffered many catastrophic in-flight failures and had a high crash record. Pan Am lost one every year they operated. The major carriers were delighted to get rid of them when the all-jet Boeing 707 came online.

The Atlas Corporation buy-in was a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Atlas was controlled by venture capitalist and corporate raider Floyd Odlum. He was married to famed aviatrix Jackie Cochran, a contemporary of Amelia Earhart. Cochran, with the help of Chuck Yeager, became the first woman to break the sound barrier. Odlum had previously been involved with Howard Hughes and TWA deals. Atlas had purchased the cash-rich aircraft brokerage firm and parts supplier, The Babb Company, after the death of Charles Harding Babb in November 1952. After selling off the assets of the Babb Company, Odlum merged it with Transocean. The following statement from the 1954 Atlas Corporation Silver Anniversary Report gives insight into how Atlas operated.

… “a special situation as Atlas uses the term, means an investment in and involving not only primary financial sponsorship, but usually also responsibility for management of the enterprise.” This typically involved reorganization, mergers, or other measures to strengthen the company and commitment “to stay with investment until the essentials of the job have been done, and to move on to another special situation.”[8]

Atlas Corporation made huge profits by buying and merging large companies and selling off divisions and assets that were worth more separately than the sum of their total. The stock of the remaining shell would be sold to unsuspecting investors.

The End of Transocean

When the CAB did approve Nelson’s request for Asia routes at the end of 1959, it was too late. Transocean was under the control of Floyd Odlum. On 11 July 1960, Transocean’s contract with the Department of the Interior to fly the ‘Trust Territories” airline in the South Pacific expired. It was given to Pan Am. Transocean declared bankruptcy and ceased operations. It had 3.000 employees and 28 bases worldwide when Atlas Corporation began selling it off. The Stratocruisers Nelson had acquired were sold to aircraft broker Lee Mansdorf, who enticed Jack Conroy to use them as the base to create the Aero Spacelines Super Guppy transports. Overseas Airlines took over the Transocean route network, leaving it with only 12 aging aircraft and no routes.

In a unique twist, the Trust Territories SA-16 Albatross operation, which Nelson had set up in 1949 for the UN and Department of the Interior, was the last to go. It was transferred to Pan American Airways, but Transocean continued to operate the Trust Territories service for 90 days until Pan Am could take over.

Nelson had worked tirelessly to get what he believed to be needless government restrictions on supplemental carriers removed. He believed they were designed in favor of scheduled legacy airlines. Public Law 87-528 was passed on 10 Jul 1962, which established a permanent role for the supplemental carrier. It proved Nelson was right, but it was too late to save Transocean.[9]

Air Systems (Aeronaves de Panama SA)

Orvis Nelson was not going to let the collapse of Transocean be the end. He continued to campaign for Congress to eliminate the CAB and deregulate the airline industry, while creating another cargo carrier. In 1962, he founded Air Systems, which was registered in Panama as Aeronaves de Panama for licensing purposes as a country of convenience. It has been rummored that Aeronaves de Panama was a company set up for nefarious operations, including the CIA, but no hard evidence was found to substantiate the suggestion.[10] There were other aircraft operated by questionable individuals registered in Panama to the company.

Somehow, Nelson was able to acquire financing for at least three Douglas C-74 Globemaster military transports with options for more. These were the predecessors of the Douglas C-124 Globemaster II. They were very large heavy-lift aircraft that were really not suited for commercial operators. Nelson acquired them from the Pan American Bank of Miami, which was pleased to get them off its books. The bank had gained possession in a judgment in September 1960 against the Akros Dynamics Corporation that defaulted on payment. Akros was a questionable operation financed with Teamster pension funds set up and run by Jimmy Hoffa to sell the surplus military transports to Fidel Castro and/or Fulgencio Batista in their battle to control Cuba.[11] The C-74s (HP-367, HP-379, HP-385) Nelson purchased were never operated in Panama. Nelson had secured a contract to transport cargo from Denmark and the Netherlands throughout Europe and the Middle East. He had established many contacts around the world during the Transocean days. The C-74s were to transport dairy cattle from Denmark to Tehran, Iran, and Saudi Arabia to build up the Middle East dairy herds. [12]

Three of the C-74s were brought back to airworthy status and flown to Europe to begin cargo service. An option was placed for a fourth aircraft. The military had maintained the C-74s well, but Akros-Dynamics had not serviced them, and they had been sitting for many years. This did not seem to affect Nelson. He had purchased military transports before and was able to bring them up to airworthy status. However, this was a different situation. The 68 DC-4s that Transocean had operated were reasonably economical aircraft to maintain with (1,200-hour) TBO P&W R-2000 engines. The C-74 was a “heavy” aircraft with (900-hour TBO) P&W R-4360 engines, which were 25 percent less usage and required constant maintenance and care. The last of three Air Systems C-74s arrived at Copenhagen in March 1963 to begin charter service, moving cattle to the Middle East.

Hank Warton Escapades

Transocean’s government and military contracts were charters of every description, which exposed Nelson to “black ops” and the nefarious world of aviation. Somewhere along the way, before 1963 and as early as 1959, Nelson met Henry Arthur “Hank” Warton (Heinrich Wartski), a soldier of fortune type who lived in Miami. Warton grew up in Germany and escaped the Nazis in 1938 to Colombia, eventually arriving in the United States via Cuba. He was a very experienced pilot who spoke fluent German. Warton became an operative for the CIA who carried out many missions on behalf of the agency. Orvis Nelson’s friendship with Warton almost cost him his life.

Lockheed Corporation had constructed two large transports for the U.S. Navy, designated as the R6V Constitution, which were delivered in 1949. The two aircraft were only operated by the Navy for two years because they proved to be underpowered and too expensive to operate. They were retired for lack of spares and parked in Arizona. In 1957, they were sold to Air Displays, and one was flown to Florida and the other to Las Vegas. The one in Florida was registered as N7376C and ended up at Opa Locka airport. In June 1963, HankWarton purchased Lockheed R6V N7376C for forty thousand dollars. It was to be flown to Barcelona to be turned into a restaurant. Warton made a side deal with Orvis Nelson to buy the P&W R-4360 engines as spares for his C-74 operation out of Denmark. Nelson saw this as a good deal to obtain spares at bargain prices, and he would not have to pay for them to be shipped from the U.S. to Europe.

A 90-day Temporary Sojourn Permit was issued by the FAA for Warton to ferry the R6V to Barcelona on 26 June 1963. The ferry flight was set for 14 July 1963 with Hank Warton as pilot and L.J. Bomback as co-pilot. Two flight engineers were hired, but both, suspecting a scam and knowing Warton’s reputation, refused to fly unless paid in advance. This put Warton in a predicament because this is a large aircraft with very few qualified F/Es available. In the evening of 13 July airport patrol saw smoke coming from the aircraft. Fire-Rescue was called, and the fire was extinguished with foam. The insurance claim showed Henry A. Warton was to collect $182 thousand for the loss of the aircraft. The fire was determined as arson because the investigation found a small hole drilled in a fuel transfer line and rags wrapped around it. Evidence of a lit candle was nearby. The Florida State Attorney charged Warton with arson, but he had escaped to Europe.[13] Orvis Nelson did not get the engines he desperately needed.

Air Services Livestock Flights

Meanwhile, in Europe, Nelson’s livestock transport C-74 could accommodate 60 cows (in calf) or 68 horses. Nelson was also transporting anything from ship parts to livestock anywhere, anytime. There were reports of poor maintenance practices on the C-74s. The crews reported problems with the props being corroded, out of time, and in poor condition. One of the aircraft suffered a fire in the Number 3 engine en route to Istanbul with a shipment of 40 cows. It had to return to Copenhagen on three engines because there were no spares. Danish authorities were beginning to question Air Systems’ maintenance practices. There were reports that a full set of C-74 manuals had never been received from Akros Dynamics when purchased. There were mentions of manuals not being supplied when Akros Dynamics owned the aircraft. The crews were using weight and balance tables from the larger C-124 Globemaster, which was derived from the C-74. This error would prove disastrous.

Air Systems C-74 HP-385 departed Tirstrup, Denmark, on 09 October 1963 with a crew of four, a veterinarian, and an observer who was associated with the Danish government. The aircraft carried a consignment of 56 pedigree Jersey cows (in calf) and four bulls destined for Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. At 01:15 am, the aircraft arrived at Marignane Airport in Marseilles, France, for a planned fuel stop. The aircraft left the ramp and was cleared by ATC for runway 31R to take off over the water for Cairo. The crew misunderstood and turned right on the taxiway to runway 13L, taking off toward the mountains. At 03:48 am, the overweight C-74 took off to the Southeast. Once airborne, the aircraft overshot the turnoff point to clear the mountains, barely clearing a 700-foot ridge. About seven miles out, it made a sharp right turn and slammed into an 800-foot-high cliff about 15 feet below the summit. All on board perished. One of the engines was found two miles away with one of the four propeller blades missing. It is not conclusive, but it is believed that the overweight aircraft suffered a catastrophic propeller failure on climb-out. One of the four propeller blades separated, causing an out-of-balance condition that ripped the 7,900-pound engine from the wing. The loss of weight caused the left wing to rise, putting the right wing down, the overweight aircraft rolled into an unrecoverable slide impacting the terrain.[14]

The Danish authorities immediately revoked Air Systems’ license and banned them from operating commercial charters out of Denmark. Nelson had the other two C-74s ferried from Denmark to Milan, Italy. The crew left the aircraft and immediately boarded a commercial flight to London, abandoning the aircraft.

After the collapse of Air Systems, Nelson returned to lobbying the CAB to deregulate supplemental carriers. His goal was still to resurrect Transocean. Nelson was picking up hours flying for several DC-4 carriers including Interocean in Europe and the Congo when he once again became involved with Hank Warton. Warton had been a pilot for Continentale Deutsche, which was formed in 1958. He had logged almost 1,400 hours with the carrier in DC-4s. In June 1960, he joined Syrian Airways and possibly was spying for the Israelis on Syrian cargo operations.[15]

African DC-4 Operations

By the middle of 1961, Hank Warton had formed an air operation named Atlanta Airways, also operating as Africa Air and Trans Africa Airways. SABENA Airlines subcontracted to Hank Warton for a DC-4 to operate UN peacekeeping (ONUC) flights in Leopoldville, Congo. Warton convinced former Continentale Deutsche navigator Burt Katlin, who also had CIA ties, to come and work for him on this lucrative African enterprise. Katlin was an outstanding navigator who had worked for New York-based DC-4 and ATL-98 Carvair operator Interocean on ONUC charters. In a strange coincidence, Interocean had begun operations by leasing a DC-4 from Orvis Nelson’s Transocean Air Lines. Even more strange is the fact that Interocean’s sister company, Intercontinental, based in Luxembourg, purchased another DC-4 N30045 in April 1960 from Orvis Nelson’s failing Transocean Air Lines for the Interocean ONUC contract in the Congo. Nelson had acquired the aircraft from his former employer, United Airlines. Hank Warton also picked up flights from time to time with Interocean, flying with Burt Katlin. Coincidentally, Katlin maintained an office in Brussels in the same building as Interocean.

Hank Warton lost his Congo DC-4 contract because his financial backer pulled his support. Warton then decided to start a DC-3 operation transporting flowers from Albenga, Italy, to Nuremberg, Germany. He managed to acquire a DC-3 but crashed it while practicing landings at the small field. In 1961.

Two Seven Seas Airline C-46 aircraft (one leased) had been confiscated by the Congolese government. The aircraft probably remained there until the Katangan secession ended in 1963. Burt Katlin learned of the leased C-46 and hatched a plan to recover it since it appeared Seven Seas had defaulted with its 1961 demise.[16] He planned to take up the aircraft lease for his cargo operation. He managed to recruit Orvis Nelson to slip into the Congo and fly the aircraft to Albenga, Italy.[17] Burt Katlin and Orvis Nelson agreed to use the C-46 for a cargo contract to fly flowers to Germany. After getting the C-46 to Albenga, Katlin discovered the Seven Seas lease was questionable and without clear ownership. He could not get it properly registered.

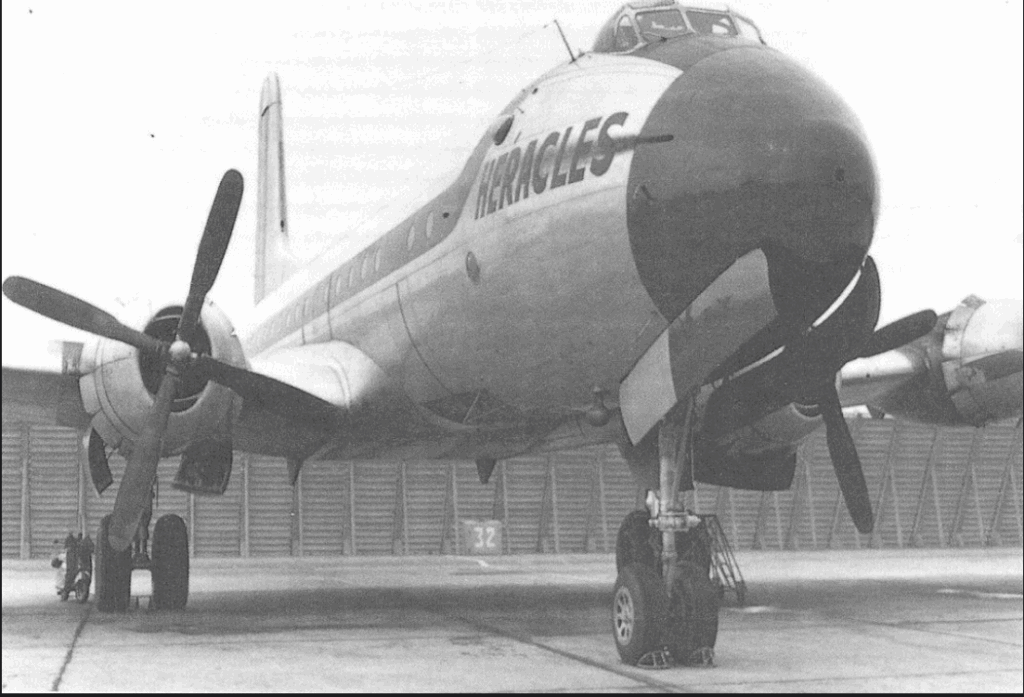

While attempting to get a clear title, it was parked at Albenga next to a DC-4M2 that Hank Warton had acquired. Warton had obtained the aircraft in a scheme he had devised with the Tutsi King of Burundi to set up a national airline. The ex-Trans Canada DC-4M was formerly with Overseas Aviation and partially owned by German entrepreneur Heinrich J. Heuer. Warton had a financial interest in the aircraft when Heuer was extradited to Germany to face charges of fraud. Warton managed to get the aircraft papers as payment to assume the balance owed on the aircraft. The ownership is quite sordid. It had been bought by Mike Keegan (yes, BAF Carvair operator and Transmeridian owner) and parked at Newcastle (UK), then held under a Court Order. Warton somehow got it released and re-registered in Panama as HP-925, then flew it to Limburg, Netherlands. It was re-registered as BR-HBP and flown to Albenga, Italy.

Warton had enticed Burt Katlin to navigate for him on his African venture. However, Katlin received a call from the CIA to fly a DC-7 to Tokyo. He suggested that his partner, Orvis Nelson, who was getting the C-46 ready for their flower operation, fly with Warton on the DC-4M until he got back and they were able to get approval for their C-46.

In the meantime, an element in Eastern Nigeria had begun an arms build-up for a planned secession as Biafra. Warton was known as a ‘dark ops’ pilot who would fly anything anywhere. Nelson’s had flown U.S. government charters of who knows what in the past. On 08 October 1966, Warton and Nelson flew the DC-4M, now registered as I-ACOA, out of Albenga on what was supposed to be a local test flight. However, they continued to Nice, where they met with an international arms dealer. They received partial payment for a cargo mission before continuing to Rotterdam-Zestienhoven airport. All the next day, crates marked machinery containing 3600 machine guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition were loaded on the aircraft. Dutch authorities were skeptical of the cargo and denied the export license for ‘machinery’ to Africa. Orvis Nelson and Warton almost got caught when one of the crates was dropped and broke open. Somehow, they were able to distract the Dutch authorities as the crate was recovered and loaded. The export papers were changed to show the shipment was going to Birmingham, UK. Surprisingly, the Dutch authorities accepted the new paperwork.

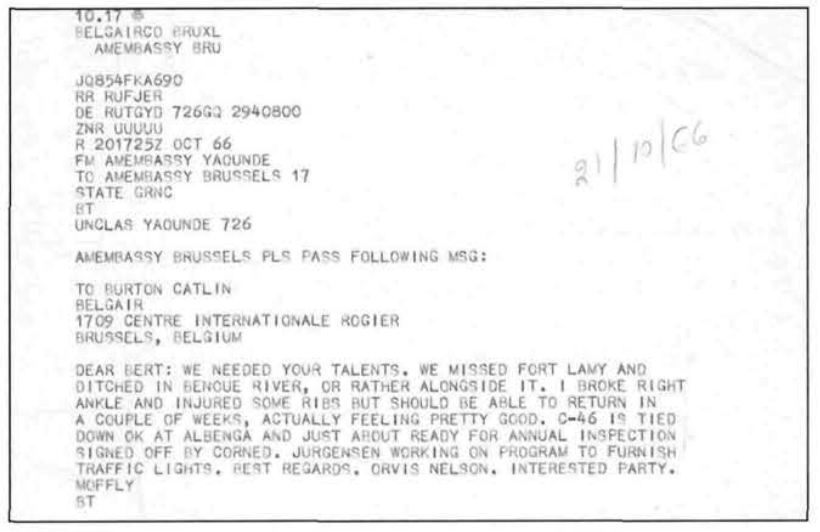

Finding a qualified navigator who knew Africa to replace Burt Katlin on a “black-ops” mission to Port Harcourt, Nigeria proved unsuccessful. Warton and Nelson, who had navigation skills, were committed and decided to go without him. They left Rotterdam with two other unidentified crew members and flew to Palma de Mallorca, Spain, instead of Birmingham as the papers stated. The aircraft was refueled and continued on a rather circuitous route to Tamanrasset, Algeria, across Niger, and to Fort Lamy (N’djamena), Chad. They were flying west en route to Port Harcourt. Neither of them knew the area and the lack of maps made it impossible without an experienced navigator. After passing over Garoua, Cameroon, they navigated by landmarks, flying above the Benue River. Fuel consumption was high because they were not flying the most direct route, and they had lost orientation. The engines of the DC-4M began sputtering as they ran out of fuel and ‘dead-stick’ crash on to a remote prairie beside the Benue River west of Garoua, Cameroon. The aircraft broke into four pieces, but there was no fire because there was no fuel. All four on board survived the crash. Warton and Nelson were both seriously injured. In addition to cuts and bruises, Hank Warton suffered a back injury that would affect him for the rest of his life. Orvis Nelson broke his right ankle and multiple ribs. Local natives were the first to get to them. The locals notified a doctor who had to come by canoe and overland to reach the crash site. Stretchers were made from the lids of the gun crates to carry them out and back to a hospital in Garoua, Cameroon.[18]

Arms smuggling carries severe penalties and prison time in Cameroon, but neither ultimately suffered any punishment. Cameroon authorities and the press in other surrounding countries stated that the pilot and co-pilot suffered severe injuries and later died in the hospital. An obvious ruse because dead men don’t talk.[19]

Orvis Nelson and Hank Warton had been charged with multiple offenses by the Cameroon authorities, but they were “dead.” Both checked themselves out of the hospital as soon as they could hobble. Cameroon officials allowed them to move around Garoua unmonitored on the condition that they would not try to leave the country. Unnoticed, Warton’s girlfriend flew into Doula, Cameroon, and booked herself passage on a ship bound for Europe. Somehow, she managed to get Warton across Cameron from Garoua and smuggle him into her cabin as a stowaway.[20]

Orvis Nelson was left behind. He sent a Telex to Burt Katlin via the embassy in Brussels. Katlin, however, was not yet back in Brussels. He was stuck in Tokyo with an engine failure on the CIA DC-7, which had originally prevented him from being the navigator on the arms flight. Nelson admitted they had made a mistake by not waiting for him to navigate the trip. There are no details on how Nelson managed to get out of Cameroon. It has been suggested that Katlin managed to influence the situation through his CIA contacts.

Nelson returned to Brussels to get the C-46 ready for the planned cargo operation. However, he and Katlin were contacted by a representative from Interocean Airways in New York who had a deal to purchase the C-46 with the questionable title. The two Interocean officials who came to inspect the aircraft were immediately arrested by the Albenga authorities. Once authorities were assured they had nothing to do with the DC-4M gun running incident and monies owed were satisfied on Warton’s overdue accounts, the C-46 was released. Interocean agreed to pay Katlin $33,000 for recovering the aircraft and the maintenance that had been done. This put Nelson out of the partnership.

In between Transocean and the Air Service cattle disaster, Nelson had continued to lobby the CAB to deregulate the airline industry. After the Hank Warton fiasco in Africa, he returned to the U.S. to continue his quest with Congress and the CAB for deregulation. He maintained that airlines should be able to operate on any route where they could make a profit.

Nelson’s Transocean Airline powerhouse had fallen prey to government bureaucracy and regulation. His attempt to start over with a small cargo operation only got him caught up in “soldier of fortune” operations. By the end of 1966, Orvis Nelson gave up flying and moved back to Minnesota. After a year in Minnesota, he moved back to California, where he worked as an air transport consultant.[21]

Orvis Nelson passed away from a heart attack on 02 Dec 1976. Two years later, the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 phased out CAB control of the airlines, allowing the air carriers to operate in a free market. Orvis Nelson never lived to see the benefits of his struggle to deregulate the airlines.

R.E.G. Davies, who was the Air Transport Curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, summed up Orvis Nelson’s life by stating the following:

“Orvis Nelson was possibly the greatest of all airline promoters who never reaped the just rewards of his enterprise, innovation, and determination.”

** Uncredited photos: Transocean, Arue Szura

References:

Bulatov, B., “Werewolves” (Moscow, Gudlok, Russia, 17 Jan 1971); 37. CIA FOIA. https://www.cia.gov.readingroom/documents.

Dean, William Patrick. The ATL-98 Carvair: A Comprehensive History of the Aircraft and All 21 Airframes. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2008. 76, 128.

Dean, William Patrick, Ultra-Large Aircraft 1940-1979. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2018. 57-63.

Draper, Michael, “Hank Warton – His early days, Super Constellations and the Biafra Arms/Relief Airlift,” Air Britain Archive (Winter, December 2012): 155-164.

Draper, Michael, “Burt Katlin’s Story,” Air Britain Archive (Summer, June 2013): 53-59.

Launius, Roger D., “Orvis M. Nelson,” in Encyclopedia of American Business, The Airline Industry. New York: 1992. 309-312.

Launius, Roger D., “Transocean Airlines,” in Encyclopedia of American Business, The Airline Industry. New York: 1992. 459-460.

Thruelson, Richard, Transocean, The Story of an Unusual Airline. NewYork: Holt, 1953.

Seven Seas Airlines, Inc., Freedom of Information Act Reading Room. CIA FOIA. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/document/06896827 08 Aug 2025

Szura, Arue, Folded Wings, A History of Transocean Airlines. (Missoula, MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1989).

Transocean Airlines 1946-1960 https://www.taloa.org/the-trust-territory 06 May 2025

Novell, Robert, Transocean Airways – A Look Back. https://www.robertnovel.com/transocean-airways-a-look-back-march-27-2020/, 06 May 2025.

[1] W. David Lewis. “Edward V. Rickenbacker,” Encyclopedia of American Business, The Airline Industry. (New York: 1992), 402-404.

[2] Roger D. Launius. “Orvis M. Nelson,” Encyclopedia of American Business, in The Airline Industry. (New York: 1992), 309-312.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Transocean Airlines 1946-1960,” https://www.taloa.org/the-trust-territory 29 April 2025.

[5] Launius, “Orvis M. Nelson.” 309-312.

[6] Ibid., 311.

[7] Ibid., 311-312.

[8] Floyd B. Odlum, Papers 1892-1976, www.eishenower.archives.gov/research/finding_aids/pdf/Odlum_Floyd_Papers.pdf,08 December 2016,2.

[9] Launius, “Orvis M. Nelson.” 313.

[10] Air Britain Archive No 1. 1990, Fact File, Part 1. 7-8.

[11]William Patrick Dean, “Ultra-Large Aircraft 1940-1979.” (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Inc., 2018). 49-60

[12] Ibid., 57-63.

[13] Air Britain Archive No 1. 1990, Fact File, Part 1. 7-8.

[14] Dean, “Ultra-Large Aircraft 1940-1979.” 61-62.

[15] Michael Draper, “Hank Warton-His early days, Super Constellations, and the Biafra Arms/Relief Airlift,” Air Britain Archive (Winter, December, 2012). 156.

[16] William Patrick Dean, The ATL-98 Carvair (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company 2008) 76,128.

[17] Michael Draper, “Hank Warton-His early days, Super Constellations, and the Biafra Arms/Relief Airlift,” Air Britain Archive (Winter, December, 2012). 158.

[18] Draper, “Hank Warton-His early days, Super Constellations, and the Biafra Arms/Relief Airlift,” 158.

[19]Bulatov, B., “Werewolves” (Moscow, Gudlok, Russia, 17 Jan 1971); https//www.cia.gov.reading.room.docs 2-3.

[20]Michael Draper, “Hank Warton-His early days, Super Constellations, and the Biafra Arms/Relief Airlift,” 158.

[21] Launius, “Orvis M. Nelson.” 313.

Be the first to comment